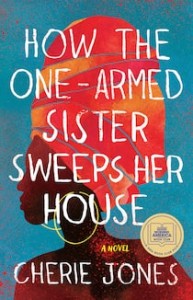

This debut novel with an intriguing title is set in Barbados in 1984 where Lala makes a living braiding hair for tourists on the beach. She lives right there in a rickety shack with her husband Adan, a petty thief. Eight months pregnant, she strains to manage the steep, railingless stairs to their home.

When she goes into labor she struggles through the night looking for her husband. Washing up against a gate in the tourist enclave, she rings the bell, only to have Adan himself appear. As they race to the hospital on his bicycle, Lala hears a scream, one that will echo in her throughout the book.

We move between Lala and Mira Whalen, originally a poor white from Barbados, whose wealthy white English husband Peter has been killed in a bungled robbery. The couple has come to Barbados on holiday, Peter hoping to win back Mira’s love after she’s had an affair. Even as the two women highlight the differences between wealthy tourists and poverty-stricken Bajans, Mira’s grief and regret resonate with Lala’s increasing recognition of the mistake she made in marrying the sociopathic Adan.

Jones deftly weaves in stories of Lala and Mira’s mothers and grandmothers and how their lives echo—or not—their daughters’. Jones also brings in other other characters such as Adan’s friend Tone, whose concern for others contrasts with Adan’s violence.

And there is a lot of violence. This is a terrible and devastating story, certainly centering on threats women face, but also touching on men and the things they are driven to do. We move back and forth in time, unearthing secrets buried too long, coming to know all these characters. This book is a brilliant example of how to bring in backstory: only telling us a story from the past when we need it to understand something that is happening in the present.

I listened to the audio book, not sure at first how far I wanted to go into such a story, but found myself riveted by the prose and seduced by narrator Danielle Vitalis‘s voice. It was so soft and lilting, so gentle that I sometimes had to shake myself to remember that these were stories of abuse and injustice and helplessness in the face of danger.

My only quibble with the book is that the ending tied everything up a little too fast and a little too neatly.

If you are willing to face the underside of life on a Caribbean island and recognise that poverty’s insults and injuries aren’t that different even in paradise, this is the book for you. Gorgeous prose, great pacing, vivid characters: this first novel has it all, if you can bear it.

What first novel have you read that you thought brilliant?