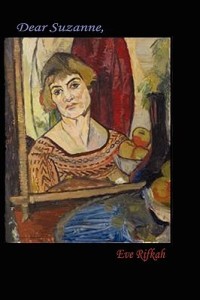

I’ve read this slim volume several times and will probably continue to reread it. Rifkah alternates poems in the voice of artist Suzanne Valadon with prose sections by a present-day narrator, apparently Rifkah herself, that read like prose poems. Together they create a multi-faceted portrait of what it means to be an artist, a mother, wife, granddaughter, lover.

In summoning the spirit of Suzanne Valadon, Rifkah explores what it means to be a woman and an artist, unappreciated, known mostly for her work as a model for artists like Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Berthe Morisot. Rifkah imagines how Suzanne herself might have described her sacrifices for her husband André Utter and damaged son Maurice Utrillo V, both artists, Maurice being better-known than Suzanne until recently.

Grandmother and Grandson the last painting of Madeleine

age 79….her mind wrapped in superstitious wandering.

Her face turned away from Maurice

away from love shredded by madness

……….they suffer each other in ache

captured by daughter and mother

a trinity tied in paint *

This poem, which ends with Madeleine’s death, is followed by Rifkah’s description of her own mother’s death. By combining Suzanne’s voice with her own, intertwining their stories, generating resonances, Rifkah has created a stunning exploration of a multitude of family relationships.

Yet Rifkah also goes beyond this handful of lives to look at the freedom sought by an artist. Like Suzanne who did not change her name with marriage, Rifkah discards her father’s and husband’s name, “becoming me alone. We change our name to change the road we travel from birth.”

I appreciate the need to define your own life, free of society’s plan for you, having come of age during feminism’s second wave when all the old models for a woman’s life went out the window and we had to create our own.

Back then, I read biographies of women artists and writers, looking for ideas. Now I read them with appreciation for the difficulty of the task. Rifkah examines the deep urges that motivate an artist, whether of words or paint, even when you see your intensely imagined works outsold by others’ scenes that are taken home by tourists “to say they’d seen Paris.”

When my model leaves

fingers still tingle

……….brushes stay fast to my hand

like the girl in the story dancing in enchanted shoes

until feet cut off

Read this book to learn about Valadon. Read it to learn about being an artist. Read it for the pleasure of the lines and sentences.

Have you ever read a novel or biography in verse?

*Note that the dots are meant to indicate spaces.