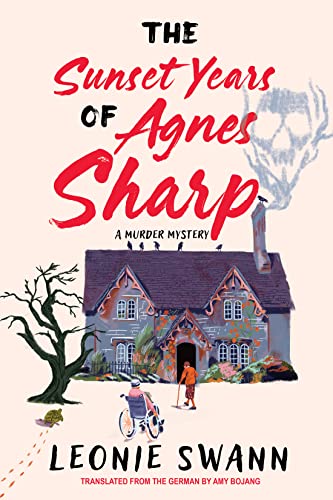

There’s a body in the woodshed at Sunset Hall, Agnes’s home that she’s turned into co-housing for other elderly folks. They include Bernadette who’s blind, wheelchair-bound Winston, flighty Edwina who practices yoga and bakes impossible biscuits, and Marshall who sometimes goes off into la-la land. And of course Hettie the tortoise.

Agnes already has a lot on her plate: finding her false teeth, the occasional ringing in her ears that renders her temporarily deaf, and having to take the stairs when the doorbell rings because the stairlift is broken. The door turns out to be the police to tell them about the fatal shooting of a neighbor, Mildred Puck. The murder may be a solution to one of Agnes’s problems. To add to the confusion, a new resident arrives: Charlie who has a fabulous wardrobe, a mind as yet untinged with dementia, and a dog named Brexit. Then Marshall brings in his grandson Nathan without prior authorization. The television gets moved to the basement, but not because of the grandson.

A lot of quirky characters, but it’s easy to keep them straight in this fun mystery. The way they have to navigate their disabilities adds a bit of shading to the story, along with a lot of unexpected suspense. I quickly became attached to these pensioners, and their surprisingly shadowy pasts.

I’ve been thinking about a post I read recently by Leigh Stein. She discusses John Truby’s idea that a story should have a designing principle, some way of organising the story as a whole. It can be the way it uses time—such as the film Titanic which unfolds in real time—or the perspective from which it’s told—such as Darling Girl, by Liz Michalski a story of Peter Pan from the point of view of Wendy’s granddaughter.

The designing principle is like a plot twist but in the story as a whole, in the story’s premise. In this cosy mystery, the first twist is that the amateur detectives are elderly. We’ve seen that before, from Miss Marple to the Thursday Club mysteries. So the second twist is that almost all of them are disabled in some way that affects the plot. And then the third twist is that they all have unexpected pasts.

I enjoyed this mystery a lot, though it took me a while to work out what rules had been established by the residents for their co-housing situation at Sunset Hall. This is what Ray Rhamey calls an information question rather than a story question. Withholding information about the world of the story creates irritation rather than the suspense we get from true story questions (what’s going to happen next?). Aren’t you wondering why the corpse is in the woodshed? That’s a story question all right. This is a small quibble, and not something that I have to worry about as I chase down the rest of the series.

Have you read a story where a tortoise plays an important role?