Most people are familiar with Andrew Wyeth’s painting Christina’s World at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. However, little has been known about Christina Olson herself aside from the fact that she had a degenerative muscular disorder that eventually made her unable to walk. Another tidbit of knowledge has been that Wyeth often painted not only Christina and her brother, but also the house on the Olson farm in the small town of Cushing, Maine.

My interest in Andrew Wyeth’s work intensified when I visited a 2014 exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Looking Out, Looking In concentrated on Wyeth’s paintings of windows. I already loved his famous Wind from the Sea, and became fascinated by his spare watercolors of other windows in the Olson house and others nearby. There are no people in these works, but their lives are somehow embedded in these spaces.

In his Director’s Note to the catalogue, Earl A. Powell III calls Wyeth’s window paintings “skillfully manipulated constructions deeply engaged with the visual complexities posed by the transparency, beauty, and formal structure of windows.” For my part, the theme named in the title remains a powerful one. Whether we are looking out or in, we see both the wide outside and the very personal interior. Also, I am deeply in love with houses, especially those which hold the story of my life.

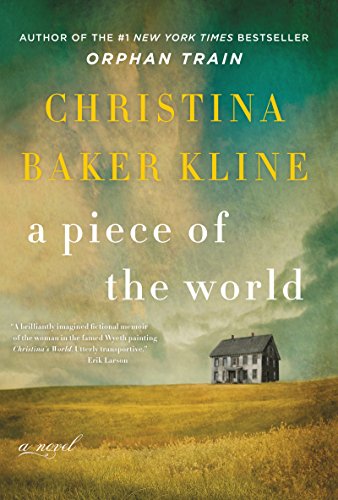

In this novel, Kline has taken the woman whose image is so familiar and opened her life to us. In her own words, Christina recounts her childhood as a smart girl who wanted to become a teacher but had to leave school to help at home. She has a brief period of social life and a chance at love before her increasing disability keeps her tied to the farm while her friends went on to marry and have children. When one of her friends marries Wyeth, he and Betsy begin spending summers in Cushing, and he starts painting at the Olson’s.

It is Christina’s voice, though, that fascinates me. Amid the constant domestic toil, the brief joy of sweetpeas blooming, the interactions with her parents and brother, her growing friendship with Wyeth, her voice is genuine: stoic and reserved, occasionally ecstatic. I felt as though I lived through each day with her, each turn of the season.

I am wary of novels with real people as characters; it feels like an invasion of privacy to create a story of someone without their permission or knowledge. However, I loved Kline’s thoughtful understanding of what it might mean for a sensitive young woman to have to live such a restricted life—not just her physical restrictions, but also the small town, the confining house, the loneliness as friends and neighbors pull away. I had a tiny surprise: the Olsons were related to Nathaniel Hawthorne, as I am myself, making Christina perhaps a distant cousin.

The limitations of her life mean the story is thin on plot, and Wyeth himself is but a minor character. The real joy of this story for me is the immersion in this woman living a life I could so easily have fallen into. In the story, Christina says of the famous painting:

He did get one thing right: Sometimes a sanctuary, sometimes a prison, that house on the hill has always been my home. I’ve spent my life yearning toward it, wanting to escape it, paralyzed by its hold on me. (There are many ways to be crippled, I’ve learned over the years, many forms of paralysis.) My ancestors fled to Maine from Salem, but like anyone who tries to run away from the past, they brought it with them. Something inexorable seeds itself in the place of your origin. You can never escape the bonds of family history, no matter how far you travel. And the skeleton of a house can carry in its bones the marrow of all that came before.

Have you read a book inspired by a painting?