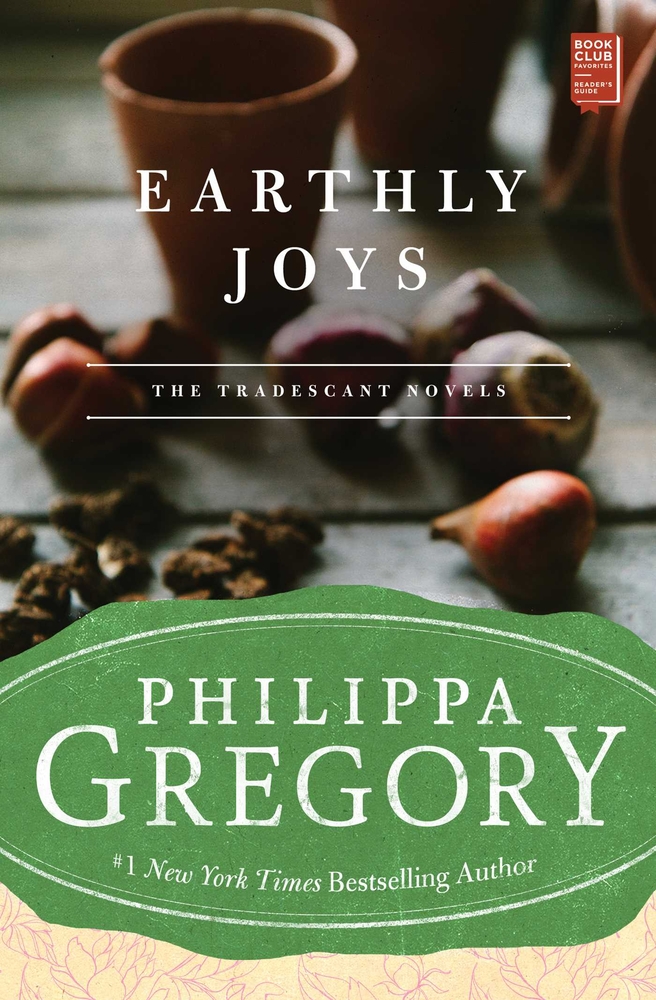

We meet John Tradescant, gardener to Sir Robert Cecil, as he discusses the state of the gardens with his master in preparation for the visit of the new king: James I. Since Queen Elizabeth died without heirs, James—son of Mary, Queen of Scots and already King of Scotland—has ascended to the throne of England. The story is told by John himself, who is based on the real John Tradescant the Elder, the most celebrated horticulturalist and naturalist of his age.

As a gardener, John has no power in politics; he keeps his gaze focused on the plants and trees that he loves. However, knowing that “he could keep a secret, that he was a man without guile, with solid loyalty,” Cecil uses this principled and practical man as a sounding board, confiding that he has been working in secret to prepare James Stuart to rule in England. James brings two great advantages: he already has two sons and a daughter, and he is Protestant. Thus, it’s assumed he will end the turmoil over the succession and the bitter and deadly religious wars.

John is asked to design magnificent gardens at Hatfield, Windsor, and others. In his work for Cecil and later other lords and James’s successor Charles I, John is sent abroad in search of rare plants. His finds are described with such care that I could see, smell and feel them: the smoothness of a horse chestnut seed, the rainbow sheen of tulips, the scent of cherry blossoms. It turns out that he loves traveling and finding exotic varieties of plants and rarities, much to the dismay of his wife and son, left at home.

This book was recommended to me for its evocation of Tudor and Stuart era gardens, making it an appropriate read for this blossoming midsummer. I was also intrigued by my memory of Gregory’s amazing nonfiction book Normal Women that spoke to the range and depth of her research into the period. What I didn’t consider was how much the concerns of people in 17th century England would echo ours today.

As they discuss the new king, John tells Cecil, “When you have a lord or king . . . you have to be sure that he knows what he’s doing. Because he’s going to be the one who decides what you do . . . Once you’re his man, you’re stuck with him . . . He has to be a man of judgment, because if he gets it wrong then he is ruined, and you with him.”

And James is not a man of judgment. He immediately begins plundering the treasury Elizabeth amassed to protect England, squandering it on his own pleasures and rewards to his friends, while ignoring the discontent, poverty and starvation of his subjects. A favorite emerges in his hedonistic court: the Duke of Buckingham: young, beautiful, and self-indulgent. After Cecil’s death, Buckingham brings John to work for him as gardener and personal servant, even taking him into battle.

Civil war is brewing, as the people protest. Parliament is furious when the King takes over their power to impose taxes and sends them home as no longer needed. The King then gets needed income by selling baronetcies and other dignities. Many begin to question the traditional concept of the divinity of kings, seeing James as not someone ordained by God, but rather as simply a man and a repulsive, dishonest one at that.

John, however, is loyal, too loyal according to his wife. John is challenged not just by her, but also by his increasingly radical son who argues that people should be free to obey their own principles, not be ordered what to think by kings and lords. While John’s obdurate loyalty to his masters—even when he thinks they are wrong—can be frustrating for a reader today, it reflects the culture of the time, which was only just beginning to hear the whispers of the individualism we take for granted today.

Another aspect that is true to the time but troubling today is the quantity of foreign plants that John introduces to England. Many have become common to English gardens and forests today, but I couldn’t help thinking about the dangers of invasive species: plants and creatures that originally seemed innocent or useful but have become a nightmare.

While politics and philosophy struck surprisingly close to home for me, they took second place to the gardens. I luxuriated in descriptions of planning everything from orderly knot gardens to seemingly natural meadow gardens. I felt I was laboring along with John and his wife and son to build these joyful works of art.

Are you a gardener?