While I love a realist novel that pulls me right into someone else’s life, like Stoner by John Williams or Migrations by Charlotte McConaghy, I also like to be surprised and challenged sometimes.

Here a woman named Elizabeth, in a story written by an Elizabeth, summons her past: “If only one knew what to remember or pretend to remember. Make a decision and what you want from the lost things will present itself. . . Perhaps.” What arrives is a kaleidoscope of people she’s known, places she’s lived, literary references, letters, brief essays: vignettes presented in prose as concise and brilliant as poetry, connected by threads so fine as to be invisible.

Elizabeth writes about her mother: “I never knew a person so indifferent to the past. It was as if she did not know who she was.” She writes about friends, such as Alex who has never quite fulfilled his promise—“Not quite liking himself, he whom everyone adores”—or Louisa who “spends the entire day in a blue, limpid boredom. The caressing sting of it appears to be, for her, like the pleasure of lemon, or the coldness of salt water.” And Billie Holliday with her “ruthless talent and the opulent devastation.”

I was most interested in the parts about two women who once worked for her: Ida when Elizabeth lived in Maine, and Josette when she lived in Boston, summoning the shape of their lives in spare sentences. Josette, who “in her passionate neatness, adored small spaces” finds her dream home in a trailer. In Maine, Ida is the “rough and peculiar laundress” whose “disaster” is the disreputable local man who moves in with her:

Winter came down upon them. The suicide season arrived early. The land, after a snowfall, would turn into a lunar stillness, satanic, brilliant. The tall trees, altered by the snow and ice, loomed up in the arctic landscape like ancient cataclysmic formations of malicious splendor. The little houses on the road . . . trembling there in the whiteness, might be settlements waiting for a doom that would come over them silently in the night.

This passage takes me back to my first winters in New England, fifty years ago now, when winters were more severe. Or at least that’s how I remember them. I have mixed feelings about her portraits of certain women. Anything that reduces individuals to categories rubs me the wrong way, yet the descriptions themselves are piercing.

I like to remember the patience of old spinsters, some that looked like sea captains with their clear blue eyes, hair of soft, snowy whiteness, dazzling cheerfulness. Solitary music teachers, themselves bred on toil, leading the young by way of pain and discipline to their own honorable impasse, teaching in that way the scales of disappointment.

Like Elizabeth, we find roots of our identity in the people we’ve encountered during our lives and in places. She writes of the Kentucky of her childhood and sojourns in Amsterdam. But it is New York City that is most vividly rendered here.

The spotlight shone down on the black, hushed circle in a café; the moon slowly slid through the clouds. Night—working, smiling, in makeup in long, silky dresses, singing over and over, again and again.

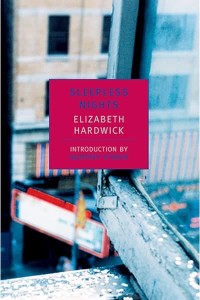

Originally published in 1979 as a novel, Hardwick’s plotless book is now considered an early work of what is now called autofiction where the lines between autobiography and fiction are blurred by writers like Rachel Cusk, Karl Knausgård and Ben Lerner.

Readers prospecting for details of her life may find fragments in their sieves: “I was then a ‘we.’ He is teasing, smiling, drinking gin after a long, day’s work . . .” The absence of the narcissistic ex-husband who co-opted her life is refreshing.

I mistrust autofiction, though I do recognise that we create our lives and curate our memories of them. I appreciate, particularly in these days of flagrant misinformation, the attempt to tell the truth.

Still, I enjoyed this fragmented chronicle of a life. Partly it’s the writing, and partly it is honoring the collection of seemingly random memories. Many of us, as the decades pile up behind us, look back and try to find coherence in the jumbled chaos of our days. Like Elizabeth we are:

Looking for the fosselized, for something—persons and places thick and encrusted with final shape; instead there are many, many minnows, wildly swimming, trembling, vigilant to escape the net.

Have you read anything by Hardwick, either her essays or novels?