Before leaving the Transcendentalists, I wanted to reread this young adult book where I first heard about them. I discovered it one cold, rainy day at Whippoorwill Girl Scout camp where—having escaped from the prescribed activities—I was poking around some bookshelves in a dark corner of the hall. Behind some mildewed Readers Digest Condensed Books, I found this book, the corners of the cover frayed by mice, the pages brown-spotted with damp. I hid behind a chair and got through the first seven chapters before being discovered by one of the leaders and told to put it back.

It took me almost two years to find the book again and read the rest. I couldn’t remember the title or the author’s name, only the story, and after a while I began to believe that I had dreamed the whole thing. When I finally came across the book on the library’s shelves, I couldn’t believe my eyes. It was as though a fantasy had suddenly become real.

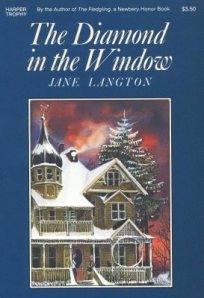

Ned and Nora live in a Gothic monstrosity of a house in Concord, Massachusetts, with their aunt and uncle. Aunt Lily teaches piano lessons to support the family because Uncle Freddy—who used to be a famous scholar—has lost his mind and spends his days arguing with marble busts of Thoreau and Emerson. The children have a run-in with a couple of town worthies who consider the house and the family a blot on their sacred soil and threaten to take the house for unpaid taxes and burn it down.

The children discover a mysterious room at the top of the house with some dusty toys and two twin beds. Confronting Aunt Lily, they learn that Lily and Freddy’s youngest sister and brother had gone missing from that room as children, followed by Lily’s sweetheart, Prince Krishna. Ned and Nora decide to sleep in the room themselves. In their dreams, they are plunged into magical adventures, adventures which turn dangerous.

There are a few books I read as a child whose images have become so ingrained in my thoughts that they have become part of my private mythology. This is one of them. It wasn’t until I was grown and had read Emerson and Thoreau for myself that I recognised that each adventure embodies one of the Transcendentalist ideas and images, such as the rough wooden harp the children find while climbing in an elm tree, an aeolian harp, although it is not named in the book. The wind blowing across the harp strings translates the voices of nature into sounds they could understand: “‘These trees and stones are audible to me,'” as Uncle Freddy quotes Emerson.

The adventure that I think about most often, though, is the one where they go into a mirror and find two statues of themselves, two of Nora, two of Ned, a little older than their current age. Ned and Nora separate, each choosing one of their statues. Behind that one stand two more. Their choices eventually lead them to statues of themselves as adults, at which point they are able to see if they have chosen wisely. Unlike real life, though, they are able to go back and make different choices.