The title of this collection of poems by Albanian poet Lleshanaku intrigued me. The title poem, itself long and complex, about her childhood and the Cultural Revolution of 1968, a result of Communist Prime Minister Hoxha’s anti-religious policy of Enver Hoxha, Albania’s leader from the end of WWII until his death in 1985.

But I found a different perspective in the poem “Menelaus” where she writes using as a persona the Spartan leader who fought in the Trojan War under his brother Agamemnon and eventually married Helen after the sack of Troy. In Lleshanaku’s telling, not only is his ship becalmed on the voyage home, but actually never arrives in Sparta:

I continued to wander on open seas, forgotten,

on history’s waters . . .Patris now doesn’t exist.

Not because of a curse from the gods,

but because with revenge

everything ends. The curtain falls.

And peace is never a motif.

“Patris” is the Greek word for homeland and of course also reminds us of Paris who started the war by stealing Helen. What I see here, though, is the enduring legacy of Albania’s civil wars, dictatorships, occupations, massacres, followed by four decades of communism and the empiness left after its defeat. How do you write about the traumas that shaped your life when they are over? In “The Deal” she talks about going home and all that has changed:

“I’ve come to write,” I explain.

“Is that so? And what do you speak of in your writing?”

asks my uncle, skeptically . . .Only my eyes haven’t aged, the eyes of witness,

useless now that peace has been dealt.

What’s left in that negative space are the small, human things of life, beautifully rendered in other poems here, with a turn that lifts them out of the ordinary. For example, in “Small-Town Stations” she pulls us in with the first line: “Trains approach them like ghosts.” Then come the details, rousing our own memories of train journeys and what we see looking out at these stations. She ends, though, with a twist that makes us rethink the entire poem and the person narrating it.

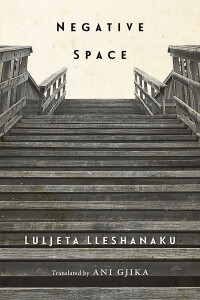

This book is Ani Gjika’s 2018 translation of Lleshanaku’s 2012 and 2015 collections. As always, I wish I could hear the poems read in the original as well, since I’m curious about the musicality of the author’s poetic voice and am never sure how well it translates.

Regardless, I’m grateful for these translations that have given me access to these poems with their images upon images. They’ve stirred me into, not only remembering my own moments and reviewing what I know of Albania’s history, but also making me think further about the long-term effects of trauma, whether it’s systemic racism or the wars and dictators who are driving the many people deciding to try the difficult journey to another country.

What do you know about Albania? Have you read Lleshanaku’s poetry?