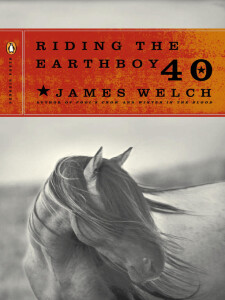

Reading and rereading this sole collection of poetry by Native American novelist and poet James Welch has been an adventure. Welch is considered to be a founding author of the Native American Renaissance in literature. The book’s title refers to the land he grew up on: forty acres leased by his parents from a family named Earthboy on the Gros Ventre Reservation in Montana. It’s a prosaic explanation for a phrase that conjures so many associations.

Steeped in the Blackfeet and A’aninin cultures of his parents, he attended schools on the Blackfeet and Fort Belknap Reservations before attending high school in Minneapolis. The tension between the Indigenous world and the White world can be found in these poems, but there is so much more.

I don’t pretend to understand all of them. Many of the poems seem like, as James Tate says in his introduction, a kaleidoscope of images. What comes through most clearly to me is the connection to the land, whether we’re talking about the stark power of a butte or the iron cold of winter in the far north. “Thanksgiving at Snake Butte” begins:

In time we rode that trail

up the butte as far as time

would let us. The answer to our time

lay hidden in the long grasses

on the top . . .

Welch moves around in time with the ease of a storyteller, conjuring a memory of three boys who barricaded themselves inside a grocery or finding the truth behind a photo in a hotel lobby. There is much about death and hardship and betrayal, much about violence done to and done by.

But there’s far more about the strength of tradition and community, even if sometimes that legacy must be questioned. He tells stories of individuals like Doris Horseman, Deafy, Eulynda, Bear Child, Lester Lame Bull. In “Blackfeet, Blood and Piegan Hunters” he says “Comfortable we drink and string together stories” of the past, but insists

Let glory go the way of all sad things.

Children need a myth that tells them to be alive . . .

He writes of small moments that take on grandeur of “Such a moment, a life.” And there’s also much about the lonely road to yourself. From “Blue Like Death”

. . . Now you understand:

the way is not your going

but an end. That road awaits

the moon that falls between

the snow and you, your stalking home.

Moons slip through these poems and “stars/that fell into their dreams.” There are single phrases that haunt me, even when I cannot grasp the poem as a whole, such as “Man is afraid of his dark” and “No dreamer knows the rain.” “To stay alive this way, it’s hard . . .” and “goodbyes creaking in the pines” both conjure strong memories.

I will keep reading and rereading these poems, letting them sit within my consciousness, within my dreams.

Have you read the work of James Welch or of another poet of the Native American Renaissance?