Today I’m giving away food.

I volunteer with a local nonprofit, Edible Brattleboro, to plant help-yourself gardens around town and, from July through October, operate a weekly Share the Harvest stand where we give away vegetables donated by farmers at the end of the farmers’ market, harvested from our gardens, and donated by local gardeners. This COVID year, when so many are struggling, we’re also part of the town’s Everyone Eats program that funds restaurants to make meals to give away.

Trying to get by on food stamps back when I was on welfare opened my eyes to the hunger in this prosperous country, now broadened to food insecurity. That first winter I quickly realised that most fresh vegetables were too expensive for my tiny food stamp allotment, so I relied on the cheapest things I could find, like carrots, cabbage and turnips. I also put the tops of the root vegetables in a saucer of water and used the fresh greens that sprouted.

Luckily we were not in a food desert; there was always an expensive spa a few blocks away and a cheaper grocery store within a couple of miles. However, when I didn’t have a car, walking to the grocery could take all morning, and I could only carry what would fit in the stroller basket and my backpack. In summer, there was no way to keep frozen food safe on the walk home.

What saved me was being able to cook.

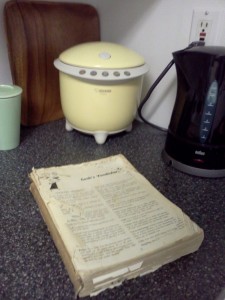

The summer I was 12, my mother boycotted the kitchen and assigned me the job of cooking dinner for our family of eight. My culinary skills were limited—I could make a sandwich, pour a bowl of cold cereal, heat up a can of soup, and make toast—but she promised to teach me. That didn’t happen. Sometimes she’d answer a question or offer a suggestion, but mostly I relied on her battered Good Housekeeping Cook Book.

Thus I not only learned the basics of cooking but also the astounding truth that I could learn whatever I needed to know from a book.

So years later, when I realised I couldn’t afford fresh vegetables, I turned to books for the new skills I needed. They taught me how to turn a vacant lot into a vegetable garden and how to can the excess tomatoes it produced. They taught me how to make jam from the wild blueberries I gathered and applesauce from seconds at nearby orchards.

Before I moved away from Maryland, I volunteered with Maryland Hunger Solutions whose motto is “Ending Hunger in Maryland”. They work with state and community partners to help Maryland residents get nutritious foods. As a former food stamp recipient I helped bring a real-life perspective.

One thing that was quickly brought home to me was how lucky I had been to be able to cook meals from scratch. Many people living in poverty either don’t have cooking facilities or never learned to cook. One food bank organiser told me she often couldn’t even give away pasta because people didn’t know how to cook it. Many people rely on expensive and less nutritious packaged foods they can simply heat up.

The founders of Edible Brattleboro—”Grow Food Everywhere for Everyone”—were inspired by a Ted talk by Pam Warhurst, explaining how the tiny village of Todmorden in England turned plots of unused land into communal vegetable gardens. We have also been inspired by Ron Finley’s work creating gardens in open land in South Central LA. He says, “Growing your own food is like printing your own money.”

We’ve also been following Leah Penniman and Soul Fire Farm, which defines itself as “a BIPOC*-centered community farm committed to ending racism and injustice in the food system. . . *BIPOC = Black, Indigenous, and People of Color”. I am especially drawn to their commitment to the ancestors. “With deep reverence for the land and wisdom of our ancestors, we work to reclaim our collective right to belong to the earth and to have agency in the food system.” Penniman’s book is called Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land.

Back when I was gardening in the vacant lot, I also got involved with a group starting a land trust, a fairly new concept in the 1970s, in the hopes of eventually renting a farm through them.

Over the years I’ve heard of land trusts for conservation purposes, but was excited to learn recently of the BIPOC Land and Food Sovereignty Fund organized by The SUSU Healing Collective, whose purpose is to help BIPOC farmers here in Vermont. There is also the Northeast Farmers of Color Land Trust. Both are worthy of our support.

Let us look for a moment at what we have in common rather than what divides us. We all need food. We all want to feed our families the best food possible and to support good causes. So I’m off to give away free food to anyone who comes by the stand.

Note: While I call this a book blog, it is essentially about stories. This post is full of them: Pam Warburton’s, Ron Finley’s, Leah Penniman’s, my own.