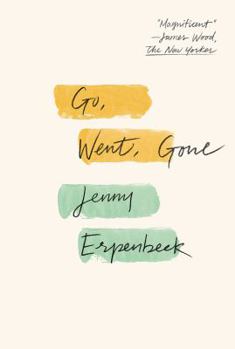

Like Antonia in Alvarez’s Afterlife, Richard, a widower, has just retired from his career as a college professor in what was formerly East Berlin.

Perhaps many more years still lie before him, or perhaps only a few. In any case, from now on Richard will no longer have to get up early to appear at the Institute. As of today, he has time—plain and simple . . . his head still works just the same as before. What’s he going to do with the thoughts still thinking away inside his head?

Such transitional moments in our lives roll grief and possibility, loneliness and freedom into a turbulent mess. The first thing in Richard’s mind, however, is the calm lake on whose shore he lives, and the man who recently drowned there, his body never found. All summer everyone has avoided the lake: swimmers, fishermen, boaters. Nobody talks about it; they just stay away. It stays calm.

On a chance trip to Alexanderplatz, he doesn’t notice the African refugees staging a hunger strike there until he sees them on the news later. He didn’t notice them because he was thinking of the Polish town Rzeszów, which had a system of tunnels, essentially a second city underground, originally built in the Middle Ages where Jews took refuge when the Nazis invaded.

Moved by the refugees’ refusal to speak or give their names, the academic in Richard stirs to life: Here is a project! He decides to learn who these men are by interviewing them. Through Richard we hear their voices, their stories, and learn about what it is to be a refugee.

I loved Erpenbeck’s Visitation and looked forward to this novel. The beginning is brilliant. Her imagery and profound insight moved me deeply and had me marking page after page. However, the story slows as Richard starts tangling with bureaucracy and coaxing the refugees to talk to him. It’s a difficult tightrope for a writer: to reflect the tedium of the situation without boring the reader.

The story picks up again as we get to know the refugees individually, and as Germany’s bureaucracy begins to close in on them, narrowing their chances of being granted residence and thereby a work permit. As a lawyer whom Richard consults says, “The more highly developed a society is, the more its written laws come to replace common sense.”

Most members of my book club agreed that, while this was a challenging read, partly because of the pacing in the middle and partly because of the subject matter, it was also an important book to read. We all learned a lot, even those who already worked in refugee services. Those who read through to the end found it a worthy cap to the story, and were moved by the generous responses of the friends with whom Richard shared his stories of the refugees.

We talked about the symbolism of the drowned man. Like the Polish city, there are hidden things here as well as things we turn our eyes away from. When do you become visible? What do you have to do?

When you do become visible, as when Richard listens to the men and shares their stories with his friends, things do change—minds change.

I also found much here about communication woven into the story. Some have to do with the refugees’ struggle to learn German and Richard’s to learn some of their languages. Some have to do with how words are like borders: mutable signs, or written in sand, the way the boy from Niger learned his own language, lost when the wind blows.

The Italian laws have different borders in mind than the German laws do. What interests him is that as long as a border of the sort he’s been familiar with for most of his life runs along a particular stretch of land and is permeable in either direction after border control procedures, the intentions of the two countries can be perceived by the use of barbed wire, the configuration of fortified barriers, and things of that sort. But the moment these borders are defined only by laws, ambiguity takes over, with each country responding , as it were, to questions its neighbor hasn’t asked . . . Indeed, the law has made a shift from physical reality to the realm of language.

The border between life and death is here too: the chances that determine which side we will land on, the ghosts that cross over. Richard is sometimes nostalgic for the lost world of his childhood in East Berlin, before the wall came down. As one member of my book club noted, perhaps that early grounding in communal living makes Richard more open to caring about the fate of these others. Indeed, the novel calls out the weakness of capitalism: its callous disregard of the common good.

As Mary Oliver asked: “Tell me, what is it you plan to do / with your one wild and precious life?” Here is one man’s answer.

What novel have you read that illuminates one of the great political issues of our time?