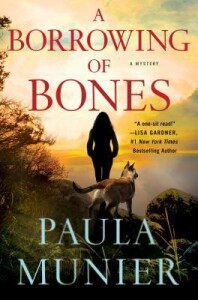

Former military police Mercy Carr and Elvis are veterans of the Afghanistan war, home now but unable to shake their habits, memories and wounds. Elvis is a bomb-sniffing dog, a Malinois or Belgian Shepherd which is similar to a German Shepherd, forced to retire due to depression after the death of his partner Martinez, Mercy’s fiancé.

They take refuge in Mercy’s cabin in rural Vermont where they have plenty of forest in which to run and hike, and Mercy’s beloved grandmother, a veterinarian, nearby. On the fourth of July weekend, they escape the fireworks and mayhem by hiking in a particularly remote area.

Then Elvis alerts that there are explosives off the side of the path. And nearby Mercy finds an abandoned baby and partially buried human bones. Her 911 call brings U.S. Game Warden Troy Warner and his partner, a Newfoundland named Susy Bear. The four of them try to unravel the mystery—Mercy leaping back into law enforcement mode and Troy reminding her that she is a civilian now.

They run into territorial disputes, including the attempts pf the state police chief to keep them out of the investigation, and hostile families on remote dirt roads who don’t try to hide their disregard for the law. The more they learn, the more they fear something terrible is going to disrupt the holiday festivities in town.

I chose this story because of the Vermont setting, and was rewarded with plenty of woodsy scenes to go with the intriguing plot. The characters also appealed to me, even the minor ones. Mercy and Elvis are sensitively drawn by the author, who avoids wounded warrior stereotypes to present realistic people. Munier also manages to handle big ideas like grief, patriotism and honor with refreshing sincerity. It’s a good reminder to me, as a writer, not to back away from concepts like these for fear they’ve been overdone.

Apparently there is a whole genre of mysteries with dogs, actually a subgenre of mysteries. The two dogs are certainly full-fledged actors in this story, and fully formed characters as well, not cutesy cartoons. Among the dogs in my life have been several German Shepherds and a Newfoundland, so I enjoyed this aspect of the story.

If you’re looking for a new series of mysteries, you might check this out. I know I’ll be looking to travel more trails with Mercy and Elvis.

t’s fun when a book has a dog who works as a character. One that comes to mind is Lessons in Chemistry. Can you recommend another?